Interview with Bo Bartlett

PPOW Gallery

Bo Bartlett: Paintings of Home

by Scott Goodwillie

December, 2010

In his recent exhibition at PPOW Gallery in New York, Bo Bartlett offered some stunning compositions which rely on childhood memories or the place of his dreams. Born in Columbus, Georgia, he depicts a world of stillness and intimacy which owes much to the insights of Andrew Wyeth who was his friend and mentor. This stillness makes the inhabitants of these paintings seem so very immediate when they make eye contact with the viewer and adds an overall haunting feel to many of the works. Being that he uses his wife in many of the works possibly intensifies the feelings conveyed.

After walking through the various rooms in the gallery there is one devoted to his sketches which don’t appear to be in preparatory for the paintings but more as studies of the human form, to keep his hand in practice. What I found attractive about these was that Bo didn’t erase the graphite traces as he was searching for the form. Usually the public is offered the finished product but with these he is, to borrow his phase, “showing one’s hand.” Around the corner we come to the last room of the gallery and it is here we discover the pearl of the show. A large work with the curious title ‘The Somnambulists’ features his models Grace and Alexis nude and in an embrace in front of another work featured in the exhibit called ‘Land of Plenty’. Upon seeing the painting for the first time with no guiding information to decipher the inherent metaphors, I was beginning to compose my own based on the seeming replacement of his wife Betsy in the piece ‘Land of Plenty’ with the Balthus like nudes in ‘The Somnambulists’. There is a case to be made here for the interpretation of any work of art which encapsulates analogy and metaphor that without the input of what the artist actually intended we can miss the mark completely. Intrigued I contacted Bo, who was gracious enough to provide me with the background and evolution of what I consider to be truly a great nude, inspired somewhat by Seurat’s painting ‘The Models’ as well as his own perceptions and the influence of those around him. What follows is Mr. Bartlett’s narrative regarding ‘The Somnambulists’;

Alexis lives on the Vashon Island- like many art students, a refugee from the art schools in Seattle. For the past few years, Alexis has always been around, posing regularly, for long painting days, morning and afternoon, drawing class in the evenings, Betsy and Anelecia and I drawing her constantly,when she is not posing or working in the office, she can be found preparing panels with 20 coats of gesso. Sometimes her sister Grace visits. They pose for drawings together. They are very close. There is a loving tenderness with no self-consciousness.

I had just gotten “Land of Plenty’ to a stopping point, when Alexis and Grace began posing for this idea. They would pose in front the other painting.At first I didn’t plan on it being a pastiche/tableaux, but once I began, I liked the layering and the meta self-referencing of the process of painting itself. I hope it takes a moment to make sense out of the composition, a moment of deciphering what is supposed to be real, and what is supposed to be painted. It is this dichotomy that the painting is meant to address. Showing ones hand. It is all artifice. The paintings are not literal, narrative, they are meant to be ‘figurative’,but not the way the term is often used in art circles, but the way it is used in literature. The paintings are ‘figurative’, like a figure of speech. They are metaphors.

The title “The Somnambulists” suggests “The Saltimbanques” by Picasso in The National gallery. They are in a Dreamland. The purpose of the Artist is to wake us up. The muses do that, but, too often, we are of an old mindset and led astray by socialization. We can’t see beauty with a clear eye. We are tainted by societal norms and ‘victorian’ and/or modernist political correctness. The same subject can wake us up or put us to sleep. It is as always the observer effecting the observed. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Artists bellow and wail, but still we slumber. Seeing the beauty of nature with pure eyes is a meditational practice. The painting suggests just how gently we can be nudged awake, and just how lucid our awakening can be.

The personality of the two figures are meant to be opposed to one another, based partly on concept and partly on the actual personalities of the two sisters. Grace, being more realistic, modern, educated; Alexis, being more romantic, soft, artful. I had many preliminary titles suggesting this dualism. A union of opposites, of world views, of temperaments. Alexis looking inward, down and Grace looking straight out, at the viewer. As always, the triangle is the over-riding compositional device, in this case, starting from our own sight lines, our point of view, we are part of the trinity, each space fractured, enfolding into smaller and smaller triangles, converging at the vanishing point, in the apex of Grace’s eye. They stand in front of “Land of Plenty”, which is based on Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Broad-Axe”.

Funny Bo, that’s exactly what I was thinking when I saw the work!

In other paintings featuring the nude there seems to be a narrative of awakening or awareness of blossoming sexuality. Choices are important when he does this and as he works with metaphor consistently it feels like the model is offering herself – and it is almost always female – exposed on a deeper level than just the physical. In a a large piece called ‘The Amorist’ Alexis is portrayed unabashed and at ease but at the same time the look on her face tells us she is waiting for someone. OK,OK that was a little too easy based on the title but there’s nothing wrong with a softball theory every now and then. Being that an amorist is someone devoted to the concept of love and especially sexual intimacy it’s a sad downward spiral from the hopefulness in this painting to other works dealing with the idealized union of opposites. There is something a bit disconcerting in many of his works in which the model, clothed or unclothed maintains eye contact with the viewer. It’s an interesting feeling in that I don’t feel this effect in the presence of an actual person, only in the artifice of a painting does this take hold. Maybe because we expect to be voyeurs while viewing a work of art and not a participant, but Bartlett choses not to let us rest but rather be engaged.

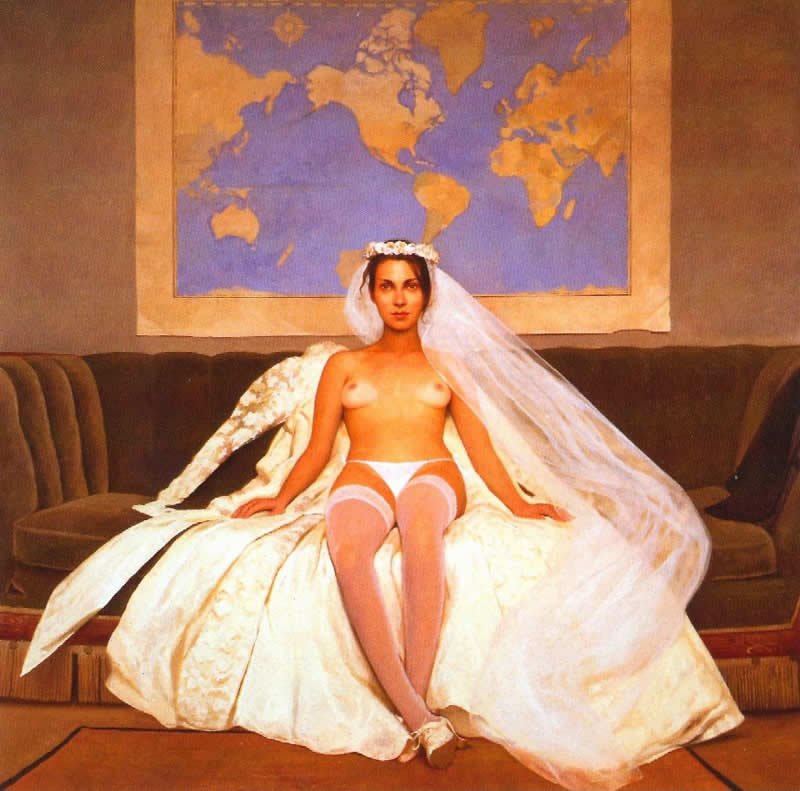

In keeping with this line of thought, we go from the budding sexuality of ‘The Amorist’ to a series of ‘bride’ paintings, possibly implying a logical trajectory in the myth of how a life is supposed to progress. In ‘Bride 1’ the young woman awaits her lover but still wearing underwear, stockings and shoes – maybe this is to imply purity – with the bulk of her gown opening up around her form like a flower and yet her legs remain closed. This is not as easy as we first suspect, some work has to be done to gain her confidence. In a marriage secrets sometimes large sometimes small are kept and a total melding is never quite complete. The sheer volume of the dress leads me to suspect that the wrapping promises more than the gift inside. The map behind her can be a reference to the “home” Bartlett often alludes to as in a reassurance of where we ought to be, but the fact that America north and south are metaphorically in the middle does nothing to say specifically where this marriage will wind up. As in Bartlett’s definition of ‘The Somnambulists’ regarding the illusion of a painted reality, here he seems to require the viewer to question the heart held concept of the real.

In a painting titled ‘Assignation’ while not a nude, completes this cycle of dashed expectations regarding marriage as the title implies a tryst. With the symbolism of the dress hung up, the woman’s spent body language and an overturned chair signaling an exit stage left, she seems to be left with the realities of her choices and is obviously not pleased. By the expression of the child standing at the open window I don’t suspect she’ll be hearing from that chap again. The old cliche is true that a work of art if it is a true expression is autobiographical, and having read about some of Bartlett’s personal history I would sum up that he works from that state of honesty, with the hopes and disappointments of life translated to canvas. While the theme running through the paintings of love and marriage ends badly, he still provides us with room to start a dream afresh with works like ‘Somnambulists’. This can be autobiographical for all of us after all, as it’s our nature to believe in new starts.