(Originally Published Sept, 2011)

This being the 40th anniversary of the “Summer of Love”, and of the concert known as Woodstock, The Great Nude felt the need to highlight the nudes of Alice Neel, one of the most independent figurative artists of the twentieth century, and an artist who’s work at this time (1960’s) reflected some of the social changes rippling through our culture.

By the end of the 1960’s Neel’s work as an artist was well known and her acceptance by the critics assured. Her career was reaching it’s crescendo, with museums and galleries lining up to exhibit her paintings. But it’s important to consider that Alice Neel started out as a woman in a man’s world under emotionally difficult if not tragic circumstances. And being a female artist who felt compelled to explore the boundaries of gender and politics, she shocked many of her peers and broke taboos with her direct and honest depictions of the nude. Her early life (and her career as an artist) was filled with many obstacles and difficulties.

We saw some of her work here in New York this summer in an exhibit at the Zwirner & Wirth Gallery. The paintings Neel produced around the 1930’s were dark and moody, a reflection of her experiences. Neel’s work at this time clashed against the social mores of this period, even by New York standards. Her paintings were often drawn from her personal experiences, where Neel’s nervous breakdown, suicidal tendencies, and subsequent internment in a mental asylum were the context from which her work as an artist began.

Neel came from a wealthy, successful family and had a relatively normal childhood. She enrolled into several art schools, but fell in love with a fellow art student, leaving school early. She soon found herself living a bohemian life with her new husband in his native Cuba, and while she wasn’t an outstanding student back in the states, she felt respected as an artist there. In 1927, Neel gave birth to her first child, and the family returned to the U.S. Tragically however, the baby died from Diptheria before the year ended. In the midst of depression and mourning, she became pregnant again. Her daughter Isabetta was born in the Fall of 1928.

Depleted and depressed, Alice returned to the States with her husband and daughter to be with her family. Alice began painting again. She had only been back a short while when her husband left her, taking their daughter Isabetta with him back to Cuba. This final loss threw Neel into a darker place, and where as a young artist, Neel’s work would take emotional root.

Eventually, the foundations of Neel’s mental health crumbled. Suicidal, she was institutionalized for over a year in a facility for the mentally insane. Neel withered away physically, while her intellect and artistic self went into hibernation. Only through a caring doctor, who recognized her artistic talent and used it to pull her back, was Neel able to recover and prove she was safe to be released to her family.

Neel lived in many of the Bohemian neighborhoods of New York City during the following decades. She was socializing with many of the city’s successful artists and writers, and openly associated herself with Socialists, Communists and Union organizers who were aggitating for aggressive social change. Alice Neel herself was an artist of the people in many ways.

Throughout the 1930’s and 40’s, Neel built a steady career of selling paintings of the people in her life to several galleries in New York, including family, friends and neighbors. Many of these people became the subjects of her figurative portraiture and often would pose for her in the nude.

She was a prolific artist during this time. As her fame and success as an artist grew, she continued to explore the nude and the use of the figure in her work. Unfortunately, many of these early works are lost to us, as an ex-lover would end up destroying over 400 of her paintings and drawings in a fit of rage.

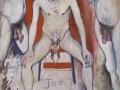

Neel’s focus on the nudity of her subjects, and in some of her works, the genitalia, often shocked the art critics. In Joe Gould, the subject sits comfortably nude, and surrounded by multiple studies of his penis. In Nadya, the model is openly presenting herself to us, but not necessarily beckoning us. Neither of these works is sexual, but both of these paintings are examples of the kinds of work that shocked Neel’s peers for their frankness, and with their perceived sexuality.

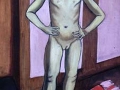

One of Neel’s most powerful figurative works, and one that she had great criticism over, was a painting of her young daughter Isabetta, who had just been returned to her mother’s life in New York.

Although Neel’s life at that time is still one of personal and professional struggle, here is Isabetta, her figure standing strong and confident, a projection of the youth and innocence. The portrait is symbolic of the promise of a healthy, normal future that a mother wishes for her child. A vision of the womanhood to come, perhaps suggesting a turnaround in both the life and view of the world that Neel sees ahead of herself.

While many of Neel’s paintings were of children and infants – the children and grandchildren of those around her – this painting in particular was difficult for the galleries to show. In response to the critique of the subject matter of nude child art, Neel says “the galleries would not show it, as they said it was indecent; by the time they showed it, they said it was Lolita.”*

In Joie de Vivre and Alienation we see images that are just as representative of the people in her life as her other, more representational works. Alice Neel’s work during this time was widely experimental in style, but she also directed her artistic curiosity at the exploration of human sexuality.

With a sense of intimacy and sensitivity – humor even – Neel illustrates human sexuality in such real-world terms, that she might even be called a Realist in her depictions what’s been going on behind closed doors of her social life. Being a woman however, we are given a perspective of human sexuality that only a woman could provide us. That’s one of the things that makes Neel’s work so ground-breaking.

As with so much of Neel’s work, emotional pain and physical challenges are channeled. In T.B. Harlem there are still the darker moods and somber tones of Neel’s early work. In this portrait, a patient who has lost a lung is recovering in a Tuberculosis Ward. Although this figure appears in great pain, he makes direct eye contact with us. Tired but enduring, he seems to be saying to us that his wound would eventually heal. He would survive.

In 1955, Neel was investigated for her involvement with the Communist party and questioned by the FBI. As with many of her portraits, and this being one of only two self-portraits of her career, Neel’s emotions are channeled directly to the surface. She paints herself bare, vulnerable, angry, in an image overflowing with personal morbidity. In this self-portrait, she is even stripped bare of her skin, the essence of her humanity.

In the the early 1960’s, the tone of Alice Neel’s work changes dramatically. Her colors become more vibrant, her figures filled with life and humanity. Calmer yet staying true to Neel’s sense of artistic honesty about painting what she sees.

The dark nature of her work is replaced with a growing warmth. Her work has an air of maturity, as her subject’s souls become easier to sense. The artist’s skills of perception at its peak. The subjects of Neel’s portraiture are confident in their identity and at ease with the artist in their nudity. This is where the element of love in Neel’s work becomes most apparent.

Neel’s work fully blossoms in this phase of her career, as her portraiture becomes filled with the lives of her subjects. She paints more pregnant women, infants and families, all symbols for life. Like Neel, the transitional undertone of her figures suggest that they have not reached their full potential, but suggest a strength in that process. Life moving forward.

By the end of the 1960’s, Neel’s career was at it’s height, and she had gained great recognition after several large museum shows of her works. Yet she still continued painting people as she saw them, regardless of their stature and place in society. Many people in the world of high-society and the world of art wanted to have Alice paint their portraits. Neel painted Andy Warhol as a tired, vulnerable and scarred figure, true to how she saw him as a man (post-operative after having been shot in a scandalous incident.)

In her last decade, aware she is nearing the end of an illustrious career as a painter, Neel witnesses the birth of her grandchildren Elizabeth and Andrew. In these figurative works of young children, so full of life and promise, a mature vibrancy is easily apparent in Neel’s work. Their new life is considered and presented to us by an artist who’s long journey is nearing completion.

Neel created only two self-portraits during her long career as a painter. One of the last paintings in her life was this self portrait painted in 1980. Although she is nearly 80, her figure radiates life. She appears composed and comfortable in her own skin, holding her brush confidently and addressing the viewer directly.

As an artist, Neel’s choice of subject was wide ranging, she would insist in later years that she didn’t see the world through the eyes of a woman, but as an artist. In practice, she had rejected the sexist stereotypes of early 20th century America and the expectations on the behavior of female artists at the time. She interpreted her subjects and analyzed her figures with sensitivity and humility that was neither male or female. Perhaps because of her personal struggles, her need to paint others became the sole cause of her compassion, and her ability to empathize with the sorrow of those around her a natural well-spring of artistic inspiration.

Alice Neel’s artistic maturity and her purpose as an artist is completed by her observing the natural cycles of human life and presenting them to us in a straight-forward fashion. The fact that Neel chose to include pregnant mothers, babies and adolescents in her figurative art works shouldn’t be proof that she viewed the world from a woman’s perspective. It should be proof that Neel the artist had concluded that the challenges in life and our true human nature are best expressed through images of motherhood, through which renewal and healing occur naturally.